Undisciplined Versions: An Ode to America

On gratitude as the confession of the subject-as-citizen

“Undisciplined Versions” will (hopefully) be the Tuesday posts of some of what I’m working on around the dissertation, and whatever other kind of research I’m doing that has to do with religion and race…gender, purity, etc. and other things. I’m hoping that this will 1) keep me accountable to making this work broadly accessible, meaningful and useful for understanding how to engage religion especially in people, places, and spaces that are unexpected. Because religion is everywhere! And it’s so interesting. When it’s not terrifying, I think.

“Undisciplined” comes from Frances Tran’s work to think with and beyond disciplinary borders and boundaries in order to imagine different ways of being and belonging in the world. I think, too, about how so much of this work is translation: a version of another version, and a conversation within a larger conversation. And, of course, I’m thinking unruly, rebellious, alternative.

—

Jeepers, late again. I was in Minneapolis for a writing cohort convened by Andy Root through a grant called “From Relevance to Resonance”. Neat chance to read and write, and to read other pastor-writers’ work on pastoral or church identity. More on that soon.

…

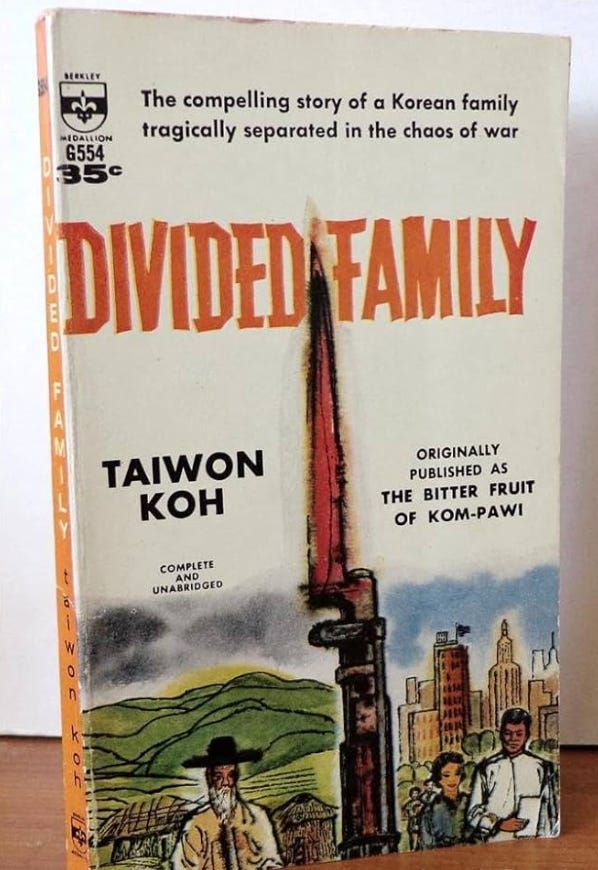

The other (immigrant) ethnic autobiography I’m working with is another under-researched/engaged story called The Bitter Fruit of Kom-Pawi (1959) by Taiwon Koh. Apparently it was republished at some point as Divided Family, as shown above. The cover is so interesting—but I don’t know what that is in the middle dividing “Korea” and the U.S.

It seems there a several versions of the autobiography, but I have a dark blue copy (below, second from left) this one (at least) has an inset by an unknown commentator (is it the author?): “Written to thank people who helped the author locate and send her three children to meet her and her husband in America, after the Korean War. The narrative is full of fascinating cultural details that describe life in Seoul in the years toward the end of the Japanese Occupation and prior to the Korean War.”

Koh’s story is similar story to Charr, albeit from a different time period and from a Korean woman’s perspective. She describes her own journey to the U.S. (being born some years after Charr) and immigrating to the U.S. a few months before the outbreak of war on the Korean peninsula in 1950. As the “Divided Family” title suggests, the story centers around her family—her family of origin and the family she and her eventual husband have and raise—and of course, the conflict on the peninsula and their immigration to the U.S.

Like Charr’s autobiography I read this autobiography as a confession, that is, another example of the religio-racializing processes of the American project towards transformation, legibility, and assimilation. The commentary given at the beginning is actually thematic throughout both autobiographies—gratitude, and the sincere expression of it.

Indeed, gratefulness as an affect—as not only feeling, but as political expression/performance, as subject formation—is theorized by Asian Americanists (particularly, in refugee studies) to be a binding force for the Asian immigrant to “America” creating structures of feeling grounded in structures of indebtedness. Giving/expressing thanks is a mode of communicating the knowledge of one’s position. In the autobiographies, Koh and Charr’s stories instantiate the various circulations of gratitude, as well as what Vinh Nguyen explains (he also has an older article on it from which I cite): “its multiple receiving objects and/or subjects. It links subjects and institutions together in the larger socio-political and cultural landscape.”

Gratitude is generated, expected and cultivated, and a feeling/emotion/experience that is an object of critique here but it can help us rethink agency and what it means for persons who are remaking their worlds.

Since I read these autobiographies as part of the religious project of America, and once more, confession as a tool and (theologically) instrumentalized towards shaping the subject-as-citizen, I read gratitude/gratefulness as a theological affect of confession. It is a major characteristic of what I’m theorizing is the “good character” (of citizenship) which these writers showcase in their autobiographies.

A gratefulness is the impetus for this written reflection on her own life in the form of this autobiography. But it is a theological expression, as it appears in Koh’s own words on page 1 of “My Christmas List”: “Such moments of undisturbed peace and contentment! I feel God close to me, and overwhelming gratitude warms my heart” (my italics). This Christian faith signals a particular legibility that is necessary—the confession of the (ethnic) immigrant U.S. American. And this confession is devotional—the story of “a girl who grew up in a remote mountainside village of Korea to the woman now living in America, the most wonderful country in the world.” It’s an expression of devotion…and loyalty. And faithfulness. It’s an ode to America.

Charr and Koh produce a particular interpretation of their lives and writing to/towards the U.S. American audience. It is in the context of engaging nation, nation-state, and national identity that these autobiographies emerge as the speaking subjects that challenge prevailing histories and memories. Their writing is not only a source of data for the formation of ethnic identity, communities and histories, but the writing itself constitutes their personhood. Charr and Koh’s stories represent the Korean figure, broadly, and these stories not only solidify, but justify their individual lives as well as by extension America as a religious project. The autobiographical form gives space to a speaking subject that both perpetuates and challenges cultural histories of Asian immigrants in the U.S. by addressing the contradictions of citizenship in their own immigration journeys.

Focusing on gender in Koh’s narrative I build on Shirley Jennifer Lim who explores the historical significance of Asian American women’s experiences through the lenses of performance, modernity, and cultural citizenship. Rather than a study of how mainstream society viewed Asian American women, Lim looks at activities on the margins in cultural venues like beauty pageants, sororities, movies, parades, and magazines to shed light on American society by probing the meanings of racially marked subjects in more “unofficial histories.”

Koh’s story provides a transpacific “unofficial history” that is a point of entry into similar kinds of performances specifically around citizenship—her position as daughter and sister, and eventually wife, her work as student, teacher and translator. In the recounting of her experiences as a female in Korea and in the U.S., Koh’s confession explores aspects of everyday life in order to perform “good character.”

I’ll tell one story for now that illustrates the compelling force of the theological imaginary of the “good character” especially in terms of gender.

Koh’s marriage to her husband Won Young is a hinge around which her autobiography turns by delineating a “before” and “after” to her identity. She is a daughter, a sister, a niece, a friend, a student, a teacher and educator, but her marriage causes much of that to fade into the background of the autobiography.

She tells the story of her arranged marriage to Won Young after her graduation from Ewha College. During this time marriages were still arranged between families. She describes marriage as an inevitability but it’s presented as a welcome contrast to the sorrow and frustration of her last three months at the college on the cusp of Japanese occupation: “One Sunday morning as I was getting ready to go to church, my head heavy with worry about my brothers’ and my own uncertain future, the loudspeaker suddenly announced that my father was downstairs.”

When she ran down to see her father she sensed something lighter about his demeanor, and the rest of the chapter details the hopeful conversations between her father and Won Young’s father, and then, her first meeting with Won Young. When Won Young finally arrives after multiple delays he describes the difficult trip (as a way to show his determination) before giving Koh a gift to solidify the marriage arrangement. She writes, “Won Young handed me his Bible wrapped in pink silk. It contained a little note that said, ‘I will try to be true to you as this Bible has taught me.” With this their engagement is announced to many relatives before he leaves for Seoul again. They were married a month and a half after their first meeting.

During this time period Koreans did not exchange rings as a sign of engagement or arranged marriage. There were numerous other gestures and rituals rooted in Confucian values around setting the date, getting permission, consulting calendars, and gift-giving. One of the final pre-ceremonial traditions involved exchanging valuables. Once the date was set, the groom sent a box to the bride with three items of which the most important were the 혼서 or marriage papers. These papers specified the name of the sender and the purpose (marriage) of sending. It symbolized the dedication and devotion of the wife to only one husband, and her loyalty and gratitude—the wife was to keep this document with her forever (these papers would be buried with her upon her death).

In this cultural context, the gift of the Bible operates in a similar way to the 혼서. Though the Bible may seem like a small and strange gesture it was a symbol of Won Young’s commitment, his duty and faithfulness to her. Her acceptance of the Bible was an expression of reciprocity of the desire to fulfill the duties and responsibilities around marriage. But, it also suggests the ways Koh makes their marriage legible not only as Koreans, but as Christians making their marriage legible (in a peculiar albeit exceptional way) as Christian to U.S. Americans. And it is an expression of loyalty and faithfulness to a particular identity. This exchange is one example of the ways religion appears in her narrative as a thread grounding her identity in marriage, family, and more broadly, in gender.

Though this story is one moment in what is the progressive development of a good character—a young, uneducated girl from Korea who eventually gets an education, gets a job, gets married and has a family, and then immigrates to the U.S. It is an example of how gratitude works, and the specific gendered expression of gratefulness, as a necessary demonstration of the subject-as-citizen that becomes incorporated into the larger U.S. body politic. Marriage (and later, family) becomes a way to express not only duty, but an extension of the institution that binds the (female) individual to the larger nation-state. It is one stanza in the ode to America.

—

Of course, in November, especially as we approach Thanksgiving, and I’m realizing now that I still have to get the turkey, I’m thinking (about) gratitude, and all the ways that we feel it, whether we’re obligated to or whether it arises “naturally” in us, and even the ways we are (theologically/spiritually/religiously) called to cultivate it in our lives. Why gratitude? I see gratitude as a grounding, a steadying, for sure, a way to not get bogged down or resigned to despair or cynicism.

But, it doesn’t mean that we can’t critique the ways it's instrumentalized (and abused) whether in larger political systems or in the interpersonal. For me, it’s a way to keep pressing towards justice, a horizon that somehow always feels just beyond our reach, but can still sharpen and deepen our work together.

Some questions to consider, in general, for reflection:

How does gratitude connect you to something bigger?

In what ways do you see the expectation of gratitude as something that undergirds certain systems? Are there programs/activities/ministries/volunteerism in which we participate where we look for expressions of gratitude (to justify what we’re doing)? Is it different for different genders? Different economic or racial groups Or generations?

How might gratitude be an expression of one’s agency?

This gets me thinking how the Gospel of Jesus Christ makes us more and less legible simultaneously.